Non capita spesso di sentire così vicine le radici da cui provieni, ascoltare delle storie di cui in qualche modo sei figlio e che nel momento in cui te le raccontano ti lasciano letteralmente senza parole. Ormai non si fugge più, ora non sono solo copertine di dischi, foto rovinate e onde che in cuffie si trasformano in musica, ora è realtà, è storia e qualcuno te la sta semplicemente raccontando. Questo è stato parlare con Danny Krivit, è stato ricostruire passo passo una parte della storia della musica newyorkese, e non solo, dagli anni ’50 fino ad oggi. Qui sotto ci sono 60 anni di musica, c’è la trasformazione della club culture da uno stato per così dire meritocratico a quello che è oggi. E’ proprio la sapienza derivata dal tempo che fa sì che le parole di Krivit sulla scena attuale pesino, eccome se pesano. Ed è un peccato che l’artista non abbia colto (o non abbia voluto cogliere) il retroscena sociale di una nostra domanda sull’evoluzione dell’uso degli stupefacenti nella realtà della musica elettronica, ci sarebbe stato da ridere. Un bambino abituato a far fronte a personaggi come Hendrix, Janis Joplin e John Lennon; un ragazzo che chiacchierava con James Brown, che pattinava e suonava al fianco di Dave Mancuso e Larry Levan in templi della Disco come il The Loft e il Paradise Garage; un uomo che ha creato una delle feste più importanti e durature della storia di New York City. Grazie alla gentile concessione di Neuhm Booking & Management, Soundwall diventa libro di Storia, mettetevi comodi e permettevi il lusso di conoscere ciò che è stato.

La fortuna ha voluto che fossi immerso nella musica fin dagli inizi. Vicini di casa pazzeschi, incontri al “The Ninth Circle” che hanno dell’incredibile, promo direttamente dalle mani di artisti del calibro di James Brown… Però, per ora, soffermiamoci sulla tua adolescenza: come percepivi la realtà da cui eri circondato agli inizi? Prima del Ninth Circle, nel periodo in cui tuo padre lavorava con Chet Baker per intenderci.

Mio padre era buon amico di Chet negli anni ’50, prima che io nascessi, e nel 58-59 gli fece anche da menager. Ma non dimentichiamoci che in quel periodo Chet aveva gravi problemi con l’eroina e questo non lo rendeva molto produttivo. Quando mio padre diede vita al Ninth Circle nel 1962 a volte ancora lavorava con Chet, ma la maggior parte del suo tempo lo dedicava al Circle. I maggiori ricordi che ho di quel periodo sono di mia madre che cantava e registrava con alcuni membri della band di Chet.

Con l’apertura del suddetto club e i tuoi primi lavori nello stesso hai avuto la possibilità di incontrare personaggi come Hendrix, Janis Joplin, John Lennon, quindi figure appartenenti ad altri mondi musicali, diversi da quello Jazz. Come hai vissuto i primi anni del “The Ninth Circle”?

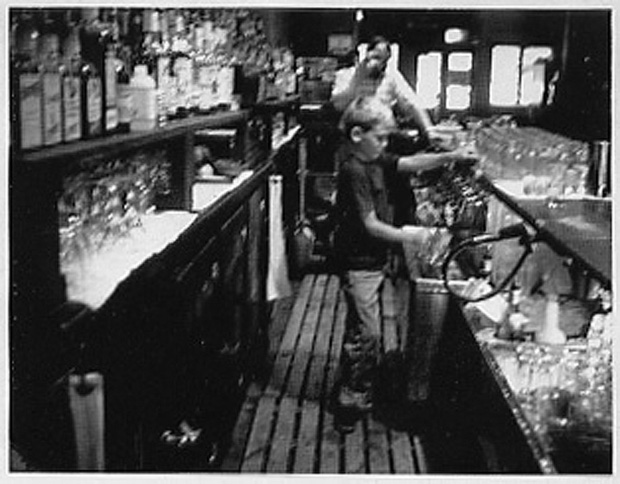

Prima di diventare un club, il Ninth Circle fu anche una steak house molto quotata per tutti gli anni ’60, quindi non era così inusuale che da bambino passassi lì molto tempo. Avevo circa 7 anni e facevo qualche lavoretto in giro per il locale e per il Sunday Brunch accompagnavo anche ai tavoli. Per due volte, durante quei Brunch, servii Jenis Joplin. Conobbi John Lennon e Yoko Ono proprio davanti al Ninth Circle, stavano facendo shopping a delle bancarelle dall’altra parte della strada… Sembrarono colpiti dal fatto che un ragazzino della mia età sapesse chi avesse di fronte. Dissi “ciao” per la prima volta a Jimi Hendrix lungo la strada e lui mi rispose “ciao”, mostrando anche lui una certa curiosità per il fatto che un bambino sapesse chi fosse. Non potrei dire di averlo conosciuto meglio di così, venne al Ninth Circle un paio di volte mentre io ero lì e ci scambiammo nuovamente il saluto. Devo dire che più che altro lo incontravo per strada intorno che al locale, non a caso gli Electric Lady Studios erano proprio a qualche blocco di distanza. Charles Mingus fu abbastanza gentile con me quando lo conobbi, più che altro perché era amico dei miei, suppongo, perché quando era al Circle non sembrava molto entusiasta di avere un ragazzino intorno, soprattutto in un posto dove andava per bere e fumare. Ma oltre ad essere un punto caldo per bohémien e beatniks di Greenwich Village, il Ninth Circle, quando si avvicinò maggiormente alla musica, aveva una bella punta di diamante. Prima della nascita delle discoteche, praticamente ogni bar e ristorante aveva un juke box e chiunque di norma, che li conoscesse o meno, poteva scegliere sempre fra gli stessi 40 brani. Mio padre trovò un posto sulla decima strada che scriveva su 45 giri qualsiasi brano volesse, così riempiva il suo juke box con musica sempre nuova, soprattutto jazz. Questo attirò molti artisti e musicisti.

In quel periodo ne avrai viste di cotte e di crude, insomma le star all’epoca erano dei personaggi interessanti e un po’… irrequieti, ecco. Per non parlare del fatto che vicino a te vivevano The Mothers of Invention! Ti va di raccontarci uno o due episodi di quegli anni che ti hanno lasciato senza parole e che non scorderai mai? Stento a credere che non ce ne siano…

In realtà, proprio perché cresciuto a Greenwich Village, non molte cose mi lasciavano letteralmente senza parole, ma i Mothers Of Invention devo ammettere che solitamente attiravano la mia attenzione. Uno dei membri, Ian Underwood, viveva proprio sotto di me e la combriccola di soggetti che lo andavano a trovare era abbastanza inusuale. Ricordo che più di una volta li ho osservati comprimersi tutti insieme dentro lo stesso ascensore, penso ci fosse la band al completo lì dentro [in quel periodo il numero dei componenti dei The Mothers Of Invention poteva variare fra i 5 e i 10 elementi!]. Io vedendo quei pazzi non volevo far altro che aspettare l’ascensore successivo, ma loro tutti in coro “dai bambino, puoi infilarti!”. Questo in un periodo in cui anche i soli capelli lunghi potevano destare attenzione… Ma quei ragazzi sembravano decisamente fuori, anche per un ragazzino come me, abituato a vedere gente strana. Loro sapevano che avevano la mia attenzione ed ho sempre pensato che un po’ ci marciassero sopra, che recitassero quella parte proprio per me. I Mothers Of Invention compressi in un ascensore non è un immagine che scorderò facilmente, grazie!

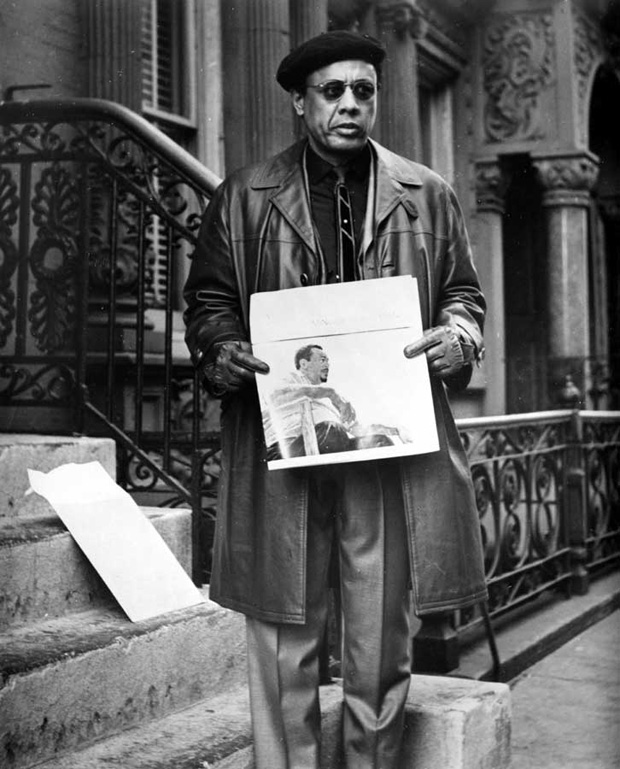

Tornando alla tua carriera, senza dubbio uno dei momenti più importanti è stato l’incontro con James Brown, reso possibile dal vice presidente della Polydor Records (tuo vicino di casa). Come ricordi quell’incontro e il momento in cui James Brown ti diede il promo del suo non ancora uscito “Get On The Good Foot”?

Jerry Scheinblum, l’allora vice presidente della Polydor, viveva proprio sopra di noi ed era buon amico di mia madre e mio padre. Sapeva che ero un dj e mi diceva sempre “quando vuoi passa su in ufficio così ti lascio qualche ultima uscita”. Alla fine un giorno passai da lui, era il 1971 e la Polydor non stava passando un gran periodo, ad eccezione che per i dischi di James Brown, lui rilasciava una o due hit… ogni settimana! Quando arrivai Jerry mi disse “tutto questo era il mio ufficio e qui dietro James ne aveva uno più piccolo. Purtroppo però per come stanno andando le cose abbiamo dovuto fare dei cambiamenti… Vabbè dai, ti faccio fare un giro per l’ufficio di James”. C’erano pile di scatole di ultime uscite di Brown ovunque, Jerry lo vide e si apprestò a presentarci. Quello fu veramente un momento particolare per me perché in quel periodo James Brown era il mio idolo supremo. Jerry gli disse che ero un dj e lui rispose “Grandioso! Dobbiamo lasciargli tutti gli ultimi James!”. Così iniziò a caricarmi di white label promo. I dischi di James Brown avevano sempre un’etichetta rossa, sempre! Non avevo mai visto un suo disco con etichetta bianca… ero in un sogno. Mi diede due uscite che gli erano arrivate proprio quel giorno: “Get On The Good Foot LP” e “Think LP” di Lynn Collins, entrambi con etichetta bianca. Non avevo mai sentito quei dischi, ma sapevo già che erano fantastici. Ero lì in piedi, stringendo e fissando il suo “Get On The Good Foot”. Lo ruotavo, lo guardavo sempre più affondo, sempre con maggior attenzione scrutavo la copertina, poi… abbassai lo sguardo… James Brown quel giorno indossava gli stessi pantaloni che aveva in copertina… pazzesco! Ho suonato quel disco all’infinito, e lo faccio ancora oggi. Questo è stato un momento determinante per me, senza dubbio; fu il momento in cui iniziai a pensare al djing più seriamente, a vederlo non più solamente come un hobby.

Leggendo di questo tuo incontro e dei white-label promo mi sono reso conto di quanto le cose siano cambiate. In fin dei conti, oggi, ottenere il promo di uno dei tuoi idoli musicali è difficile ma non impossibile. Prima si parlava di oggetti fisici che non si infilavano proprio in un taschino e che soprattutto era, diciamocelo, improbabile ottenere!

Sì, quelli erano anni d’oro e sono incastonati nella mia memoria. Adoro i miei promo, di tanto in tanto gli do anche un’accurata lucidata… Il mondo digitale ha distrutto tutto questo.

Altra figura fondamentale (per te e per tutta la scena) fu senza dubbio David Mancuso, disc jockey e padre del “The Loft”, una vera e propria Mecca del djing negli anni ’70. Cosa hanno rappresentato per te il “The Loft” e Dave Mancuso, come si inserivano nella movida newyorkese?

Per me David ed il The Loft sono le basi, le radici dell’albero cresciuto negli anni d’oro delle notti di NYC e di tutto il mondo. C’era un modello che veniva seguito praticamente da tutti i migliori club. I dj più in vista del tempo portarono questo concept dove andavano a suonare, così si iniziò a diffondere sempre più. Ecco, grazie a Dio quello del The Loft era il modello creato da David, il concept originale e non un’orribile replica.

Ho letto che durante i Loft parties di Mancuso non si vendeva da bere o da mangiare, è vero? Non lo nego, mi fa effetto pensare ad una festa con clientela senza bicchiere alla mano…

Devo contraddirti, c’era del cibo… ottimo e sano cibo gratuito e “punch” per tutta la notte, un punch che si avvicinava più ad una sostanza psichedelica che ad un classico alcolico. Tutto questo era compreso nei 2 dollari e 99 cents dell’ingresso… Ti davano un penny di resto! Inoltre ricordo che l’attenzione era tutta riservata alla musica, non al come uno dovesse essere per poterne godere… La gente era molto euforica, ma per il sound in sé principalmente. Questo erano i veri party di NYC, di questo ci si preoccupava: della musica.

In realtà non penso si possa parlare di feste pubbliche per quanto riguarda il The Loft, la clientela veniva accuratamente selezionata se non sbaglio. Penso le tue prime grandi feste furono quelle del Paradise Garage. Parlaci del tuo rapporto con il Garage e Larry Levan. Era buono “l’impianto di casa” di Larry?

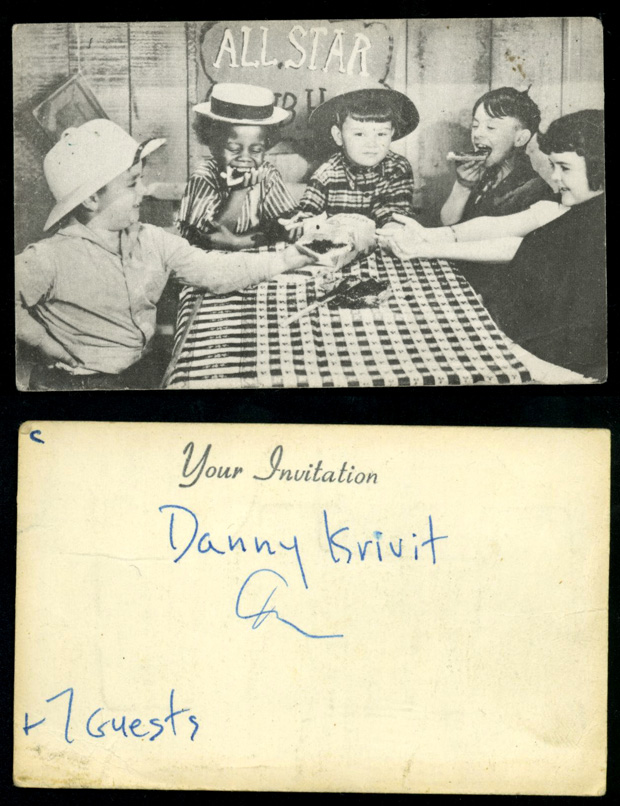

Il The Loft, il Garage e gli altri underground party di quel periodo erano tutti per lo più privati e si rispettava particolarmente il privilegio di farne parte. La gente aspettava fuori dal Loft sperando di riuscire a corrompere un membro per poter entrare, ma i soci rispettavano troppo quella realtà per fare una cosa simile, facevano entrare solo persone che stimavano veramente. Quando finalmente riuscii ad entrare correva l’anno 1975, ci vollero anni prima di trovare un membro del The Loft che garantisse per me. Quando divenni socio del club e amico di David iniziai periodicamente a portare a lui alcuni dischi per avere un parere. Sembrava veramente apprezzare sia questo mio gesto che la nostra amicizia. Ricordo che era un uomo di poche parole, era una rapporto fatto di vibrazioni il nostro. Andò a finire che mi diede un membership con +7 guest, ancora oggi mi sembra una cosa sensazionale. Una notte, mentre gli stavo portando alcuni dischi, mi accorsi che c’era qualcun altro a suonare… Mi presentai e gli chiesi dove fosse Mancuso. Mi disse “E’ laggiù, bussa alla porta!” e si presentò come Larry Levan. Gli dissi che avevo portato alcuni dischi a David e lui si fece avanti dicendo che gli avrebbe fatto piacere ascoltarli. I vinili erano qualcosa di veramente molto personale e all’epoca raramente venivano condivisi. Gliene piacquero alcuni e fu proprio quella situazione che fece sì che lui si aprisse con me, diventammo ottimi amici. C’erano stati altri grandi club prima del Garage come l’Infinity, il Le Jardan ed altri, ma erano pubblici, non per questo non buoni, ma ancora impallidiscono al confronto con il Garage. Quando quest’ultimo aprì Larry si trasferì nel retro. Mi ricordo che spesso andavo lì per pattinare. Neanche si svegliava che già stava ad ascoltare i dischi appena arrivati. Io pattinavo attorno alla pista da ballo mentre lui era lì a provare nuove uscite sull’impianto del club, come fosse il suo home stereo. La pista, per gli standard dell’epoca, non era molto grande per pattinare… ma mi sentivo in paradiso.

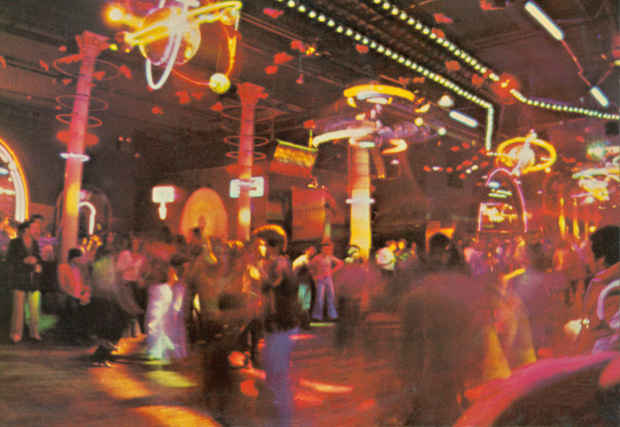

In quegli anni a NYC il numero dei club stava crescendo spaventosamente e molti lavoravano duro per avere il miglior impianto. La scelta del club era fortemente influenzata dal sound. Qual era a tuo parere il migliore e perché?

Il The Loft era il top per noi audiofili e per me è ancora così. Inoltre David sceglieva di suonare molti dischi dal suono particolare per rendere chiara la superiorità del suo impianto. Il Garage sembrava il Loft sotto steroidi: più grande sotto ogni punto di vista, il che implicava ovviamente anche un volume più sostenuto. Larry e Richard Long erano perennemente alla ricerca di nuovi modi per migliorare il sound system. Entrambi, il Garage e il The Loft, rimangono i miei sistemi audio preferiti di tutti i tempi. Senza dubbio ci sono stati ottimi sound system allora e ce ne sono stati altri con il passare degli anni, ma ancora nessuno può essere definito così maestoso, nessuno può essere paragonato a quell’esperienza totale che David e Larry riuscivano a darti.

Dopo più di 40 di djing non c’è alcun dubbio: hai visto il dancefloor in tutte le sue forme. Quali sono le differenze più grandi che noti fra la pista del passato e quella del presente? Perché la gente andava a ballare negli anni ‘70-’80 e perché lo fa ancora oggi? Pensi il pubblico sia mosso da interessi diversi?

Il tempo libero… Questa è una della più grandi differenze fra ieri e oggi, la gente prima lo aveva, ora non più. Questo e la speculazione immobiliare rappresentano i due elementi che fanno la differenza fra il presente e il passato. Avendo tempo libero la gente aveva più libertà, usciva più di frequente durante la settimana e si divertiva; in posti come il The Loft e il Garage si ballava per 12 ore filate, si tornava a casa e si replicava la sera successiva… E se non era allo stesso club ce ne erano altri centinaia dove poter andare altrettanto divertenti, economici e memorabili. Alla fine degli anni ’70 New York aveva circa 4000 club con licenza per fare cabaret e altrettanti senza… tutti sembravano destinati a non esaurire mai il loro successo. Oggi, New York ha circa 40 locali con licenza cabaret e molti fanno anche fatica a sopravvivere. Negli anni ’70, all’ottima situazione immobiliare seguiva anche una maggiore libertà artistica: i club aprivano con meno difficoltà, si potevano permettere una politica d’ingresso molto più economica e, fondamentalmente, potevano permettersi di fare ciò che consideravano più interessante secondo i loro standard personali, non secondo quelli più condivisi e accettati. In quegli anni le cooperative e i condomini di un palazzo non erano i possessori della proprietà in cui vivevano, erano considerati gente di passaggio; erano più stabili i club con i loro investimenti e se qualcuno si lagnava del locale al piano di sotto… beh, vi posso assicurare che la polizia solitamente agiva per proteggere il club. Oggi è esattamente l’opposto, sono tutti irremovibili proprietari e i club sono solo una seccatura. Ed è così in tutto il mondo, in Paesi dove c’è una buona depressione immobiliare c’è anche la possibilità di godere di una maggiore libertà artistica e le opportunità che hanno i club sono migliori. Posti come Berlino, ad esempio, stanno ancora godendo di questa situazione, ma non appena il valore degli immobili comincerà a salire, purtroppo, vedremo cambiare la scena anche lì. Questo fenomeno che ti ho appena descritto, assieme alla mancanza di tempo libero, hanno stravolto tutto dando vita a masse di individui con una soglia dell’attenzione limitata. Oggi la gente vuole rimanere immediatamente a bocca aperta, non ci si ferma per godere del tempo grazie al quale le cose maturano un gusto. Il problema di ciò è che va a generare esperienze di cui si può far benissimo a meno per vivere. E’ chiaro che questo stratagemma, questo format di emozioni usa e getta fa sì che la gente ne voglia sempre di più. Io, però, ancora mi sento di paragonare il tutto all’erba che cresce fra le grinfie del cemento… la vita trova sempre la via, le cose continuano sempre ad evolversi e possono sempre migliorare.

In fin dei conti, anche se in modi forse profondamente diversi, il dancefloor era un momento di grande importanza sociale e lo è tutt’oggi. Si dice “dimmi cosa ascolti e ti dirò chi sei”… per inquadrare ancor meglio l’evoluzione del pubblico negli anni penso sia ancora più funzionale un “dimmi qual è lo stupefacente più diffuso e vi dirò chi siete”. Verso la fine degli anni ’70 è stata emblematica la “junky moon” degli Studio 54, ad esempio. Ai tuoi occhi, com’è cambiato negli anni il rapporto fra le droghe e il mondo del clubbing?

Ciò che mi dà carica è la musica, la vita e la gente che prova queste mie stesse sensazioni. Non penso starei ancora facendo ciò che faccio se non fosse stato per questi motivi. Le droghe costituivano e costituiscono un’importante componente della realtà della notte, semplicemente non è un qualcosa che mi appartiene e di cui vorrei esser parte.

Torniamo a te ora, parlavamo del The Loft poco fa. Proprio qui iniziasti la tua lunga amicizia con Larry Levan e Francois Kevorkian, amicizia sfociata nel 1996 nelle feste “Body & Soul”. Un simbolo per la città di NYC e ormai anche per il resto del mondo. Così recita il sito “On any given Sunday at Body&SOUL, people from all walks of life, all ages, all races, raised their hands in the air and gave thanks for the unifying force that brought them back week after week: the music”. Com’è nato questo progetto? Dopo quasi 20 anni di attività definiresti ancora così il “Body & Soul”?

Io e Francois siamo amici da 35 anni. Nei primi anni ’90 lui si era concentrato più sul lavoro in studio che sul djing e quando ogni tanto suonava ci metteva tutto se stesso. Proprio perché suonava sporadicamente, era stufo di dover ogni volta perder tempo con inutili situazioni e questioni. Sapeva che io suonavo spesso e che avevo a che fare sia con gli aspetti positivi che con quelli negativi, così un giorno mi chiamò e mi disse “Ma come diavolo fai a sopportare tutto questo?”. Iniziammo a parlare di quale sarebbe stata una situazione ideale, senza pretese. Immaginammo un’ipotetica realtà in cui suonare assieme, magari di domenica, non troppo tardi, mettendo i dischi che amavamo e di cui eravamo appassionati. Lui disse che magari avrebbe inserito un po’ di drum & bass, io che mi avrebbe fatto piacere mettere su anche un po’ di hip-hop… Una situazione con non troppe persone, giusto qualche amico a cui potesse piacere la situazione, una cosa per divertisti, non a pagamento. Un giorno, nel Luglio 1996, mi chiama e mi fa “Ricordi quello di cui parlammo tempo fa?! Sto organizzando qualcosa per oggi che potrebbe avvicinarvisi molto… Perché semplicemente non vieni giù con qualche bel disco e passiamo un po’ di tempo a godercelo?!”. Questo fu il primo Body&Soul… Saremo stati circa in 30, fu meraviglioso. Lo riorganizzammo la settimana successiva e fummo circa 75 persone. La terza settimana coincideva con il compleanno di Larry Levan [morto qualche anno prima, ndr] così decidemmo di fargli un tributo e chiedemmo al nostro amico Joe Claussell di unirsi a noi. Nonostante il suo talento, Joel non era solito suonare in giro, quindi era necessaria un po’ d’azione di convincimento… alla fine decise di partecipare. Insieme raggiungemmo un’incredibile sinergia, un equilibrio che non avevo mai sperimentato con nessun altro… il resto è storia.

Altro tuo grande successo, questa volta nato nel nuovo millennio, è il “The 718 Session”. Come mai hai deciso di dar vita a questa festa, qual è la storia della nascita del “The 718 Session”?

Quando il Club Vinyl chiuse, trovammo difficoltà a spostare l’evento, non trovavamo un locale adatto, così mettemmo in pausa il progetto Body & Soul a New York continuando con i nostri eventi d’oltreoceano. Benny Sotto, manager che avevo conosciuto al Vinyl, mi parlò dell’idea di organizzare alcune feste a Brooklyn, dove il prefisso telefonico è 718. Devi sapere che a NYC sentendo quel numero si pensa subito a Brooklyn… Da qui il nome “718 Session”. Quando ci spostammo a Manhattan il concept party ormai era stabile, il nome si era affermato e infine “212 session” non funzionava bene, così decidemmo di tenerci il nostro caro vecchio 718. Questa è la festa che io considero veramente come la mia casa, ci ho messo tutto me stesso e la gente sembra decisamente aver apprezzato i risultati finali e ce lo dimostra con la sua fedeltà. Dopo 10 anni di attività siamo più forti che mai e vantiamo di esser stati insigniti più volte del titolo di “Best Party in NYC”.

Un evento che ha più di 10 anni e che ha resistito anche allo spostamento da Brooklyn a Manhattan. In una megalopoli dove ormai nulla è stabile e permanente, qual è secondo te il segreto, se così lo vogliamo chiamare, che permette al “The 718 Session” di essere così longevo?

La gente e la musica. Ormai siamo al Santos Partyhouse da un bel po’… ora che ci penso siamo stati i primi a organizzare feste lì, al tempo era ancora uno spazio grezzo, abbiamo dovuto lavorare sodo per farlo suonare come si deve. Ora hanno un ottimo sound system e solitamente suono solo con i vinili. La combinazione “vinile + ottimo sound system + ottimo pubblico” ha reso possibili molti momenti magici. Il club e lo staff sono molto ospitali e con i piedi per terra. 718 Session è pura vita, e io ne sono grato.

NYC è un un po’ l’emblema della società contemporanea, anche se ne rappresenta l’estremizzazione (cosa che New York fa con tutto!): la fretta, il cambiamento, il cosmopolitismo, i tempi stretti, l’organizzazione maniacale del tempo… Come influenzano questi fattori la colonna sonora della nostra società?

Il disagio della frenesia, della velocità… Non che io ne sia poi così indifferente. E’ solo che tutta questa velocità ha un prezzo… si perde molto e non ci si riesce ad aggrappare a nulla, non si possiede nulla. Tutto è incentrato sul cosa avrai dopo, ciò che hai ora si è già consumato.

E invece tu, come ti relazioni con questi cambiamenti? Ho letto, ad esempio, che preferisci set lunghi e questo è invece il momento storico in cui la gente vuole tutto e subito, in cui i dj si susseguono uno dopo l’altro in scalette rigidissime…

Mettere troppi dj in un’unica serata è come la differenza fra un’ottima e soddisfacente cena e una manciata di h’orderves [Hors d’oeuvres, piccoli stuzzichini]… alcuni sono buoni, altri cattivi, senza senso uno rispetto all’altro e soprattutto insoddisfacenti. Se dovessi suonare per gente che ama quest’accozzaglie di artisti so di per certo che una mezz’ora di un mio set gli sembrerebbe un’eternità. Mi trovo molto più a mio agio con persone che condividono la mia stessa passione per la musica. Amo far fare alla gente un viaggio, inviare loro un messaggio che si realizzi nella collettività e che sia più forte di una semplice canzone.

Quindi, per concludere, qual è il tuo pensiero sull’attuale scena dance?

Ho visto e sentito di tutto con il passare degli anni… Non si tratta di mode, qualcosa o è buono o non lo è. E non si tratta neanche di nostalgia, semplicemente non sopporto la musica usa e getta; non mi interessa dell’ultima uscita in sé, sono sempre alla ricerca di un nuovo brano che mi piaccia abbastanza da poterlo suonare ancora fra un anno… anche fra dieci se è per questo. Ad esempio il The Loft e il Garage mi hanno dato la possibilità di conoscere nuova musica, ma non erano solo questo, erano in primo luogo buona musica! Senza inutili etichette. Per quanto riguarda il presente: prima ti parlavo metaforicamente di quell’erba che instancabile e tignosa cresce fra il cemento, ecco, sono felice anche solo che ancora ci sia. La gente veramente appassionata c’è e sembra esserlo più che mai, questo significa molto perché oggi è decisamente più duro esserlo. Ciò che mi piacerebbe vedere è un focolaio epidemico di persone che vuole di più, che chiede sempre qualcosa di meglio.

English Version:

You do not often feel so close to roots we come from, listen to stories that somehow you are son of and that when they tell you, you remain literally speechless. Because now you can’t flee anymore, now they are not just album covers, ruined photos and waves transformed into music in your headphones, now it is History and someone is simply telling you. This was talking to Danny Krivit, it was reconstructing step by step part of the New York music history (and beyond) from the 50s till today. And it’s the knowledge derived from time that makes really serious Krivit words about the current scene. Thanks to Neuhm Booking & Management, Soundwall becomes history book: make yourself comfortable and let’s permit the luxury of knowing what it was.

Absurd neighbors, incredible meetings at “The Ninth Circle”, white-label promos directly from James Brown hands… But wait, keep calm and let’s start from your childhood: how did you live and perceive the reality you were surrounded by at the beginning? Before The Ninth Circle, I’m talking of the period in which your father worked with Chet Baker…

My father was good friends with Chet before I was born in the mid 50’s, by 58-59 it had progressed to my father managing him. But keep in mind this was also the period of time Chet was strongly in to heroin, which mostly kept him from working. When My father started the Ninth Circle in 1962 (I was 5), there was still some work with Chet, but now my fathers focus was the Ninth Circle. More in my personal memory of this time was my mothers singing & recording some of the members of Chet’s band.

With the opening of The Ninth Circle and your early little works in it, you had the chance to meet people like Hendrix, Janis Joplin, John Lennon, and figures from other music worlds, different from the Jazz one. How did you experience the early years of “The Ninth Circle”?

The Ninth Circle was also a top rated steak house restaurant all through the 60’s before becoming a disco, so it wasn’t that unusual that I would be in there a lot as a kid, as early as age 7, I was doing all kinds of odd jobs around the place, and for their Sunday Brunch, even waiting on tables. Twice at the Sunday brunch I served Janis Joplin. I met John Lenon & Yoko Ono in front of the Ninth Circle, as they were shopping in a boutique across the street, they seemed impressed that someone my age even knew who they were. I would say hi to Jimi Hendrix on the street & he would say hi back, again seemed to be slightly impressed someone my age even knew who he was. Can’t say I knew him more then that, he came in the Ninth Circle a couple of times while I was there & also said hi, but would really see him more often on the street, as Electric Ladyland was about 2 blocks away. When I met Charles Mingus, he was pleasant to me because he was friends with my parents, other then that, he didn’t seem very keen about a kid like me being around, especially in a place he came to smoke & drink. Besides being a Greenwich Village hot spot for beatniks & Bohemians, and such, the Ninth Circle also had an edge when it came to music. Before discos, practically every bar & restaurant had a juke box, and everyone (weather they knew it or not) basically had to choose from the same top 40 songs as everyone else. My father found a place on tenth avenue that would make a single 7” vinyl of any song he wanted, and he filled his Jukebox with hot new music, especially Jazz. This attracted a lot of artists & musicians.

I guess at that time you’ve seen all sorts of things. Stars of the time were interesting characters and a bit… restless, we can say. For example you lived near The Mothers of Invention apartment! Would you like to share with us one or two episodes of those years that left you speechless and that you’ll never forget? I hardly believe there aren’t some…

Growing up in Greenwich Village, not much left me speechless, but the Mothers Of Invention could usually get my attention. One of the members, Ian Underwood, lived down the hall from me, and the cast of characters that would visit him were pretty unusual. I remember more then once squeezing into the elevator with what seemed to feel like the entire band. I really wanted to just wait for the next elevator, but they were all going “come on kid, you can fit”. This is at a time when long hair alone could get a lot of attention… but these guy seemed pretty out there, even for a jaded kid like me. They knew they had my attention, and it seemed like they were usually performing a bit for me.

Back to your career, without doubts one of the most important meeting was the one with James Brown, made possible thanks to the Polydor Records vice president (your neighbor!). How do you remember that meeting and the exchange of “Get on the Good Foot” promo with James Brown?

Jerry Scheinblum, vice president of Polydor at that time, lived directly above us & was a good friend of my father & mother. He New I was a DJ & would always say “stop by my office & I’ll hook you up with our latest releases. By the time I got up to see him, it was about 1971, and Polydor was not having a great year for releases… except for James Brown who seemed to be putting out a couple of hit singles… every week. When we got there, Jerry said “this used to all be my office, & James Brown had a small office in the back, but the way things are going, we needed to switch offices… so let me show you around James’s office”. There were stacks of boxes of new James Brown releases piled up in all the isles. Jerry see’s James & offers to introduce us. This was really something, because at this time James Brown was my supreme idol. Jerry told him I was a DJ, and James said “Outta sight! We gotta give him all our latest jams”, and proceeded to load me up with White label promo’s. James Brown records always had that trademark red label, I had never seen a James Brown White label promo… I was in the clouds. He gave me two pre-leases he had just gotten in that day… Get On The Good Foot LP & Lynn Collins Think LP, both white labels. I haddn’t even heard them yet, but somehow I knew they would be hot. I was standing there holding & looking at the Get On The Good Foot LP, turning it & seemingly looking deeper & deeper into the cover… & then it dawned on me… he’s actually waring the same pants suit today that he is also waring on the cover… surreal! I played those records to death & still have them today. This was a very defining moment for me, and where I started taking DJing more seriously, and not just a hobby.

Reading of this meeting and of the white-label promo, I realized how much things have changed. After all, today, achieving the promo of one of your musical idols is difficult but not impossible, with Internet and the right email the file could be on your computer. OK, I made it easier than it actually is, but in the past promos were physical objects that you do not just crawled into a pocket and, above all, it was unlikely to get them!

Yes, those were special times embedded in my best memories, I cherish those promo’s, along with meeting the artist, sometimes even getting an advance acetate. The digital world eliminates all of that.

Another key figure (for you and the whole scene, too) was David Mancuso, disc jockey and father of “The Loft”, a real Mecca of DJing in the 70’s. What have “The Loft” and Dave Mancuso represented for you, and how did they integrate in the lively New York of the night?

For me, David & The Loft were the base of the tree that grew into the golden age of NY night life, & the world. There was a template set that was mostly adopted by all the best clubs to follow. All the best DJ’s of the day saw this too & further spread the template, & so on. Thankfully it was David’s template & not some horrible alliterative.

I’ve read that during Mancuso’s Loft Parties they were not sold alcohol or food, isn’t it? It doesn’t seem strange there wasn’t food, but… I have to admit it: for me, imagining a party without people with drinks in hands it’s something weird!

There was food… good healthy free food, all night, & “punch”, that leaned a bit more towards psychedelic then alcoholic. This was all included with the $2.99 addmission… you got a penny back 🙂 Also, remember that the focus was completely on the music, not how high you were to enjoy it… people were very high, on the music itself, this is what all the best party’s were about.

I do not think The Loft parties was public, “customers” was carefully selected, if I’m not mistaken. I think your first really great/large parties were those at the Paradise Garage. Tell us about your relationship with The Garage and Larry Levan. Was his “home stereo” good enough?

The Loft, Garage & other underground party’s of the day were mostly all private, & you highly respected the privilege of belonging. People would wait outside the Loft hopping they could bribe a member to get them in, but members respected there home too much to do that, & only sponsored someone they believed in. When I finally got into the Loft it was 1975, it had taken me several years to find a member to sponsor me. Once I became a member & friends with David, I used to bring him new records to check out. He seemed to really appreciate this & my friendship. Back then he was a man of very few words, it was a very vibey thing. He ended up giving me a membership with + 7 guests, it seemed like a big deal to me even then. One night when I was bringing him some records, someone else was playing… I introduced myself & asked where David was. He said “he’s over there… knocked out!”, & introduced himself as Larry Levan. I told Larry I had brought some new records for David but he was welcome to check them out. Records were very personal then & not often shared. He liked a couple of them & this helped him to open up a lot quicker, we became good friends. There were other big clubs before the Garage, like Infinity, & Le Jardan, & others, but they were public & as good as they were, they still paled in comparison. When the Garage opened, Larry used to live in the back. I remember often Roller skating over there. He would be just getting up & go to listen to a bunch of new records we had just gotten in from the record pool. I would skate around the Garage dance floor while he would check out new records… like it was his home stereo. By rollerskating standards, the Garage was really not that big… but I was in heaven.

In those years the number of clubs rose in NYC, and a lot of those fought and worked hard in order to have the best sound system ever! The chose of the club was deeply based on the sound it had, I think. What was the best in your opinion and why?

The loft was the best audiophile type system & really remained that way, David also chose to play a lot of exceptionally sounding records that also made that clear. The Garage seemed like the Loft on steroids, bigger in every way, which also meant louder. Larry with Richard Long were consistently improving the Garage system, throughout it’s 10 year run. Both The loft & Garage remained my all time favorite sound systems. There were other very good sound systems then & later, but still none as great, also none of them could really compare to the total experience that David & Larry would give you.

After more than 40 years of DJing there’s no doubt, you’ve seen the dance floor in all its forms. What are the biggest differences you notice between past and present? Why did people go dancing in the ’70s and ’80s, and why do they do now? Do you think the audience is driven by different interests?

Leisure time… one of the biggest differences then & now, people had it then & they don’t now. This & real estate speculation are the biggest things that effect what we had then & what we have now. With leisure time, people had time & did go out several nights a week & hang out, in places like the Loft & Garage, maybe 12 hours, & then come back & do it all again the next night. & if not there, there were countless other places to go… fun, cheap, easy & memorable too. In the height of the 70’s NY had about 4000 clubs with cabaret licences + a lot without… they all seemed to be overflowing with success. Today NY has about 40 cabaret licences, & the places that have them are struggling to survive. New York’s real estate was depressed in the 70’s, which allowed for a lot of artistic freedom, clubs could open relatively cheaply & basically do what they wanted without the big concerns of the bottom line. Before coops & condo’s people were not property owners & considered transients, clubs had an investment, & If someone complained about a club downstairs… the police would generally sided with the club. Today it is completely the opposite, everyone is a landlord, clubs are a nuisance. This is the same worldwide, places with a cheap depressed real estate can enjoy artistic freedom, & easier club opportunities. Places like Berlin are enjoying this right now, but when real estate prices go up… that will change too. The long road in getting here & the lack of leisure time, has created the “short attention span”. People today would liked to be “wow’d” in an instant, no time for an acquired taste. The problem with all this is that it leads to an experience you can very well live without. It’s clear that the gimmick & the disposable format are running thin leaving people with wanting more. I kind of think it’s like grass growing through the cement… life finds a way, things continue to evolve.

In the end, also if maybe in very different ways, dance floor was a situation with big social importance, and we can say the same about the present. Someone says “tell me what you listen to and I’ll tell you who you are”. Even better to frame the evolution of the audience (and of this world in general) over the years, I would say “tell me what was the most popular drug and I will tell you who you were”. The “junky moon” of Studio 54 was emblematic in the 70’s, for example. How has it changed over time the relationship between drugs and the world of the night?

I’m high on the music & life & relate to people who feel the same. I don’t think I would be still doing this all these years if it wasn’t for that. Drugs were a big part of night life then & still are today, it’s just not what I’m into or wanna be a part of.

We were talking about The Loft: right here you began your long friendship with Larry Levan and Francois Kevorkian, the three Djs behind the “Body & Soul” parties. A symbol for the city of NYC and now for the rest of the world. The official website says “On any given Sunday at Body&SOUL, people from all walks of life, all ages, all races, raised their hands in the air and gave thanks for the unifying force that brought them back week after week: the music”. How was this project born? After almost 20 years of activity, would you still define in this way the “Body & Soul”?

Me & Francois have been friends over 35 years. By the early 90’s Francois was more focused on studio work then DJing, & when he did occasionally DJ, he put a lot into it, & often was disappointed with what he generally unnecessarily would have to deal with. He knew I was playing often & had to deal with the good & the bad all the time. He would call me up saying “how do you deal with this”, & then we would talk about what would be the perfect situation, all the unpretentious best circumstances. We would talk about DJing together, maybe on a Sunday, not late, playing music we like & are passionate about. He said maybe he would include some Drum & Bass, & maybe I would include some choice Hip-Hop, maybe not that many people, just some friends who think like us, just for fun, not $. One day in July 1996 he called me & said, what we’ve been talking about, I’m doing something today that just could be it, why don’t you just come down with some favorite records & we’ll have a good time. That was the 1st Body & Soul… maybe only 30 people, but it felt wonderful & we did it the next week with maybe 75 people. The 3rd week fell on Larry Levan’s birthday & we wanted to do a tribute, & we thought of asking our friend Joe Claussell to join us. As talented as Joe was, he really wasn’t DJing out & needed some convicing… he ended up doing it. Together we really had an incredible synergy which I can’t compare with playing with any other DJ’s… the rest is history.

Another great success, this time born in the new millennium, is your “The 718th Session.” Why did you decide to give life to this party, what is the story of the birth of “The 718 Session”?

When Club Vinyl ended, we just couldn’t find a suitable replacement for a club, & temporarily put Body & Soul on hold in NY, only continuing our overseas events. Benny Sotto, who used to be a day manager at Vinyl approached me about doing some party’s in Brooklyn, where telephone exchange is 718, & saying 718 usually brings Brooklyn to mind… hence the name 718 Sessions. When we moved to Manhattan, the party’s were already off the hook & the name stuck, somehow 212 Sessions just didn’t cut it. This is the party I really call home, & I really put my all into this & the crowd really appreciates it & is very loyal. After 10 years, we’re stronger then ever & often voted best party in NY.

A 10 years old event that has resisted to the move from Brooklyn to Manhattan, in NYC where everything changes in months or even days! In a megalopolis where almost nothing is stable and permanent, what do you think is the secret which allows to “The 718 Session” to be so long-lived?

The people & the music. We’ve been at Santos Partyhouse for a while now, we were actually there very first party, when it was still a raw space & we had to bring in sound. Now they have a great sound system & I usually play mostly vinyl records. The combination of vinyl, a great sound system & a great crowd has made a lot of truly magical moments. The club & our staff are very welcoming & down to earth. 718 Sessions is a pure joy, I’m very grateful.

NYC is a kind of contemporary society emblem, even if it represents an exasperation of that society (something that New York does with everything!): the haste, fast changes, cosmopolitanism, manic organization of time… How these factors affect the soundtrack of our society?

Uncomfortably fast… not that I’m so different, I want things fast too. It’s just all this speed comes with a price… you miss a lot, & you don’t really grab on to anything. It’s all about what you have next, what you have now is already over.

And you? How do you relate to these changes? I have read, for example, that you like long dj set, and this is an historical moment where people want everything at once, where DJs are strictly lined up one after the other…

Too many DJ’s is like the difference between a really great satisfying dinner, & a bunch of h’orderves, some good, some bad, unrelated & overall unsatisfying. If I had to play for people who don’t get it… a half hour might feel like an eternity. It comes very easily for me to play a long set for people who share my passion for music. I love to take people on a journey, a collective connected message stronger then just a song.

So, to conclude, what is your thought on the current dance scene? What would you change or improves and what do you like?

I’ve seen & heard a lot over the years… I’m not about trends, something is good or it’s not. & It’s not about nostalgia, I just don’t care for disposable music, good lasts & I’m always looking for a new piece of music I will like enough to still play a year from now… 10 years from now. When I refer to The Loft & The Garage, they mostly turned me on to new music, but were not limited to that… they played good music!… Without all the labels. Regards to today… like the grass growing through the cement, I’m just glad it’s still here, & the people who are passionate about it seemed to be more passionate about it then ever, which is saying a lot, because it’s more effort to be like that today. What I would love to see, is an epidemic outbreak of people on a mas scale wanting more, & wanting better.